In 1951, after I had completed my articles* at Witkin, Sidelsky and Eidelman, I went to work for the law firm of Terblanche & Briggish. When I completed my articles, I was not yet a fully-fledged attorney, but I was in a position to draw court pleadings, send out summonses, interview witnesses - all of which an attorney must do before a case goes to court. After leaving Sidelsky, I had investigated a number of white firms - there were, of course, no African law firms. I was particularly interested in the scale of fees charged by these firms and was outraged to discover that many of the most blue-chip law firms charged Africans even higher fees for criminal and civil cases than they did their far wealthier white clients.

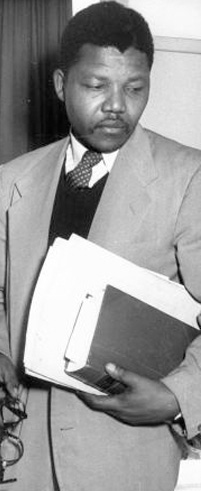

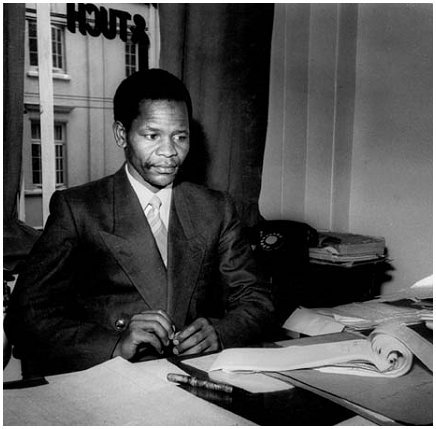

... In August of 1952, I opened my own law office. ... Oliver Tambo was then working for a firm called Kovalsky and Tuch. I often visited him there during his lunch hour, and made a point of sitting in a Whites Only chair in the Whites Only waiting room. Oliver and I were very good friends, and we mainly discussed ANC** business during those lunch hours. He had first impressed me at Fort Hare, where I noticed his thoughtful intelligence and sharp debating skills. With his cool, logical style he could demolish an opponent's argument - precisely the sort of intelligence that is useful in a courtroom. Before Fort Hare, he had been a brilliant student at St. Peter's in Johannesburg. His even-tempered objectivity was an antidote to my more emotional reactions to issues. Oliver was deeply religious and had for a long time considered the ministry to be his calling. He was also a neighbor: he came from Bizana in Pondoland, part of the Transkei, and his face bore the distinctive scars of his tribe. It seemed natural for us to practice together and I asked him to join me.

... "Mandela and Tambo" read the brass plate on our office door in Chancellor House, a small building just across the street from the marble statues of justice standing in front of the Magistrate's Court in central Johannesburg. Our building, owned by Indians, was one of the few places where Africans could rent offices in the city. From the beginning, Mandela and Tambo was besieged with clients. We were not the only African lawyers in South Africa, but we were the only firm of African lawyers. For Africans, we were the firm of first choice and last resort. To reach our offices each morning, we had to move through a crowd of people in the hallways, on the stairs, and in our small waiting room.