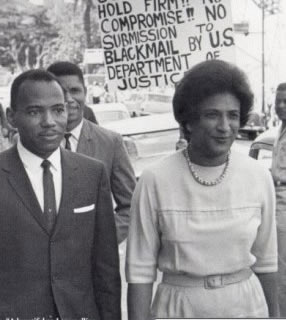

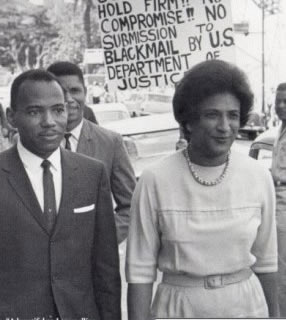

Constance Baker Motley

EQUAL JUSTICE UNDER LAW (1997)

|

Constance Baker Motley had a long and distinguished career as a lawyer, elected official and judge. She served as Chief Judge of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, arguably the most important federal trial court in the country. She was the first African-American woman appointed as a federal judge; only four other women were federal judges at the time of her appointment in 1966. She was elected as Manhattan borough president and for many years before that worked as a staff attorney with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, where she participated in Brown v. the Board of Education, argued ten cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, and represented James Meredith in his successful lawsuit to desegregate the University of Mississippi. (The Meredith case is one of the two cases we will read about in Volume II of the course case studies). She died in 2005 at the age of 84. |

College and Law School, 1941-46

On graduating from NYU in October 1943, I could not go to Columbia Law School immediately because the term had already started. So I applied for the February 1944 semester and secured a well-paying job at a new wartime agency to aid servicemen's dependents in Newark, New Jersey. The Prudential Life Insurance Company had just put up a building in Newark. When the war broke out, the federal government took over such buildings as needed for the war effort. So the government leased the Prudential building and used it for its Office of Dependency Benefits (ODB). I had a friend, Emma King (Price), from Birmingham, Alabama, who also had attended NYU, in the School of Education. She had gotten a job at ODB a few months earlier and suggested that since I had a bachelor's in economics I could get hired as an adjudicator. I applied and was hired.

When I had been at ODB a couple of weeks, I had to take a placement exam. After the exam, my supervisor, a white woman from the Bronx, came to me all excited" "You are going to get a promotion," she exclaimed. "You are going to get a promotion." I said, "Really? Why?" This was around December 1943. I said, "Because I'm going to Columbia Law School in February."

"What? That's crazy," she said. "Why do you want to waste your time doing that? Women don't get anywhere in the law. You should stay here. Women like you are moving right up here. Look at me. I am a supervisor. If the men were here right now, I wouldn't be a supervisor. When the men are here, women don't get promoted. You could be a supervisor soon." "Well, who knows when the war will be over," I replied. "The men may be back soon." "Oh, no," she insisted. "The war will go on for at least five years." Finally, I said, "I won a scholarship to Columbia Law School and I'm going." Her final words were "That's the dumbest thing I ever heard. That's a complete waste of time."

When I finally got to Columbia Law School the next February, I found - much to my surprise - that the student body included several other women like myself who were determined to become lawyers, notwithstanding the hard-nosed, antiwomen bias prevalent in the profession. There were about fifteen women there when I arrived, and the law school took in at least eight more in the middle of the year. Columbia Law School men were being drafted, and suddenly women who had done well in college were considered acceptable candidates for the vacant seats.